Poet, Scholar, Vengeful Ghost, God of Learning — Michizane is Remarkable!

Japan loves threes. Three Great Beautiful Places. Three Great Night Views. Three Great Mountains. In this three article series, I introduce you to Japan’s Three Great Vengeful Ghosts.

Sugawara no Michizane is my favorite of Japan’s three most vengeful ghosts. He was the most noble, then the most frightening, and today, he is the most honored.

Vengeful Ghost #3 — Sugawara no Michizane

Sugawara no Michizane was born into a family of mid-level aristocrats in Kyoto in 845. Both his grandfather and his father were scholars of classical Chinese literature and history, taught at the Kyoto school of higher learning, and were private tutors to emperors. Michizane was destined to surpass them.

He began reading classical Chinese poetry at age five and composed his first poem at the age of eleven. As a child, Michizane could often be found in the garden of his father’s estate, gazing at the plum trees and admiring their ephemeral, delicate blossoms while he composed poetry, a habit he continued throughout his life. Michizane grew to be the greatest composer of classical Chinese poetry in the history of Japan and the epitome of scholarship.

He began his service to the imperial court when he was 25, and quickly advanced through the court ranks. By age 33, Michizane had attained the highest level of scholarship in Kyoto.

Michizane, Friend of the Emperor

Michizane was not only respected by Emperor Uda for his scholarship, but he became family when Uda chose Michizane’s oldest daughter to be one of his concubines. Closer still, when Uda’s third son married Michizane’s third daughter.

In 901, Emperor Uda named Michizane Minister of the Right, elevating him to the second highest court rank. Soon thereafter, Uda retired, turning over control of the government to his eldest son, Emperor Daigo.

A man with whom Michizane had been on friendly terms, Fujiwara Tokihira — who held the higher position of Minister of the Left — along with many of the nobility, were not happy with Michizane’s quick advancement. Remembering his daughter’s marriage to Uda’s son, they devised a scheme to get rid of him.

False Allegations

Nobles, mainly of the Fujiwara family, accused Michizane of conspiring to make his son-in-law, Uda’s third son, emperor in place of Daigo. The accusations carried such weight that, in spite of Michizane’s innocence, he was banished to Dazaifu, a fortified governmental base in northern Kyushu.

One of the conspirators was Fujiwara Sugane, a close associate of Michizane and one of his former students. When Uda heard of the travesty of Michizane’s banishment, he sought an audience with Daigo, but Sugane would not permit him to see the emperor without an invitation. Uda sent a message to Daigo through Sugane, but Sugane never delivered it.

Misery and Death in Dazaifu

Michizane had to pay his way to Dazaifu, and once there, was provided with no attendants or salary. He was given a broken down, abandoned house in which to live. Although holding an official title, he was forbidden to work or even step foot into the government offices. He could not teach. His writings were censored.

His heart was grieved that his family shared in his punishment for his perceived disloyalty to the emperor and had been scattered. He dearly missed them.

He yearned for his life in Kyoto, his evening poetry parties, and his books. He longed for the fine food, beautiful clothes, and refined culture. He wished to sit again in his garden and gaze at his beloved plum tree, with its delicate and fragrant blossoms. So great was his yearning, legend tells us, that one night Michizane’s plum tree uprooted itself from its home in Kyoto and came to rest in Dazaifu. It is still there.

Nothing but misery, crime, and harassment befell him in Dazaifu. The local situation was so full of corruption that Michizane felt it was beyond hope. People murdered and stole without compunction or fear of retribution.

Curious onlookers came to gawk at his misery. Tokihira’s spies hounded him. The colors of his once-lovely kimonos gradually faded as they turned to rags.

As the months passed, Michizane’s money ran out. He could no longer afford food, clothing, or even a place to live. He died heartbroken and in abject poverty in 903, just two years after arriving in Kyushu.

The Fujiwara scheme to banish him from Kyoto and his work was, in effect, a slow, drawn out, and depressing death sentence.

Michizane Becomes a Vengeful Ghost

After Michizane’s death, unexplained troubles began to shake Kyoto. There were cycles of floods and droughts, plagues and earthquakes.

- In 908, Fujiwara Sugane, Michizane’s former student who had plotted against him and refused to deliver Uda’s message to Emperor Daigo, was struck by lightning and died.

- The next year, the main conspirator, Fujiwara Tokihira, inexplicably fell ill and died.

Rumors spread among aristocracy and commoners alike that Michizane’s ghost had returned to seek revenge.

The troubles continued.

- The man who replaced Michizane as Minister of the Right fell into a swamp and died while out hunting.

- Daigo’s second son died. The historical record, Nihon Kiryaku, attributed his death to Michizane’s curse-like, malevolent feelings towards the emperor. Later that year, a fearful Daigo had Michizane reinstated as the Minister of the Right.

- Before another three years had passed, the eldest son of Daigo’s recently deceased son also died.

- Next, Tokihira’s oldest son died.

Again, fingers pointed to the avenging spirit of Michizane. Anxiety and fear grew.

- In 930, a meeting was held in the great hall of the imperial palace with Emperor Daigo in attendance, along with his highest court nobles. Suddenly, a bright fork of lightning split the sky and struck the imperial hall, causing a devastating fire that killed many important government officials. Daigo, traumatized by the disaster, fell ill and died three months later.

The vengeful ghost of Michizane, embodied in lightning, had made his most powerful attack.

This had to stop.

From Vengeful Ghost to Shinto God

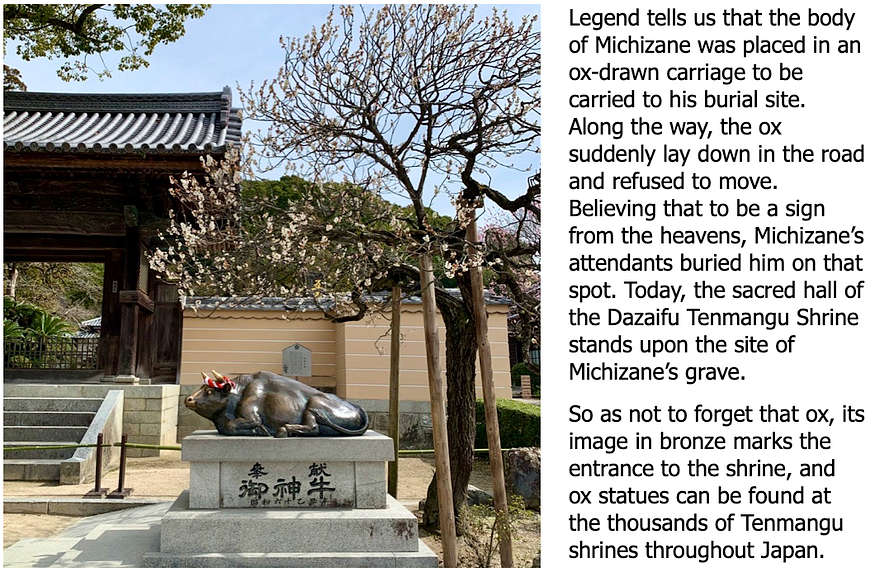

Daigo’s son, the emperor Murakami, ordered the building of Kyoto’s Kitano Shrine to house the spirit of Michizane and had him deified as the kami, or Shinto god, Tenjin, “god of the heavens.” This was the first of many Tenmangu Shrines, specifically dedicated to Sugawara no Michizane.

During the Edo era (1603–1867), the story of Michizane’s life became a popular subject of puppet and kabuki plays. In fact, the most famous of those plays, Sugawara Denju Tenarai Kagami (Sugawara and the Secrets of Calligraphy) is considered one of Japan’s Three Great Kabuki Plays. (I told you Japan loves threes.)

Outside the fanciful world of theater, Michizane came to be worshipped as the god of learning. Students prayed to him in their small temple classrooms, and samurai made offerings for his help in improving their martial arts’ skills.

Today, Michizane is known as the god of scholarship, the god of honesty and sincerity, the god of the performing arts, the god of dispelling false accusations, and even the god of agriculture.

There are approximately 12,000 Tenmangu Shrines dedicated to Sugawara no Michizane in Japan. Each year, thousands of students flock to his shrines to pray for his help in passing entrance exams as well as regular folk hoping to improve their abilities or knowledge.

I wrote about the other two great vengeful ghosts here: Taira no Masakado and Emperor Sutoku.

Sources:

https://news.mynavi.jp/article/20210930-1978876/, https://kitanotenmangu.or.jp/, https://www.dazaifutenmangu.or.jp/about/michizane

If you have questions about Japan or suggestions for articles, please add them in the comments. For more photos and information on Japan, follow me on instagram at: https://www.instagram.com/more_than_tokyo/